The emotional, physical and mental exhaustion of working with a bottom set year 11 class has its own characteristic flavour. You feel frustration at students who have switched off, annoyance at students who disturb others’ learning, fear for students who are working but not getting anywhere and, ultimately, inadequacy that you aren’t doing a good enough job.

You all know the kind of class I’m talking about, and we don’t need to go into minute and granular detail about its challenges and the characters that typically make it up. If you are going to have high expectations and standards for a class like this, you are certainly in for a challenge. I know from my own experience I’ve often felt like giving up or lowering my bar, and sadly sometimes those feelings have become reality.

I thought about having that sentence read “and sometimes I have let myself down by allowing those feelings to become reality,” but in truth I don’t know if I let myself down. It’s damn difficult trying to keep a brave face, calm demeanour and relentlessly high expectations. I reckon if anyone says that they’ve managed this the whole time they’re pulling a fast one. The perhaps unwarranted feeling of inadequacy lurks, but I think it’s important to be able to say to yourself “I’m doing all I can, and there’s a limit to what I can do.”

The above notwithstanding, it is what it is, and we need to deal with it. I think there are two very broad areas that need addressing when dealing with a bottom set year 11:

- Lack of motivation

- Lack of knowledge

These issues are of course not unique to year 11, but they do reach their peak there. These are students who, over the course of four years, have grown used to knowing little and caring less. An urgency is reached in year 11 that borders on panic: we must get these students some grades- we cannot allow them to leave school without the qualifications they need to lead happy and productive lives.

The lack of motivation and lack of knowledge are not unrelated. Often, students much earlier on in school miss out on crucial learning for whatever reason. This makes it harder for them to succeed. Experiencing failure time and again then tells them that this is what they will always feel and there is therefore no point in even trying. Obviously, it’s a little more complicated than that, but my approach to these classes tends to focus around that relationship between competence and motivation: the extent to which our competence in a particular domain affects the way we feel towards that particular domain.

Broadly, the philosophy behind the route outlined below is that helping students get good at something, helping them to feel some success, can be massively empowering and motivating, especially for students who are so unused to that feeling (more here). I really don’t want you to think that it’s a completely “fool-proof” route, or that other ways won’t work. It’s just what I’ve done and has worked a bit. It’s also not easy: it’ll take you time and perseverance as you combat deeply engrained issues and an inevitable feeling that you aren’t getting anywhere. I also have no idea if it would work outside of science as I have no experience of that. With those provisos in hand, I hope it helps.

- Get yourself a list of Core Questions

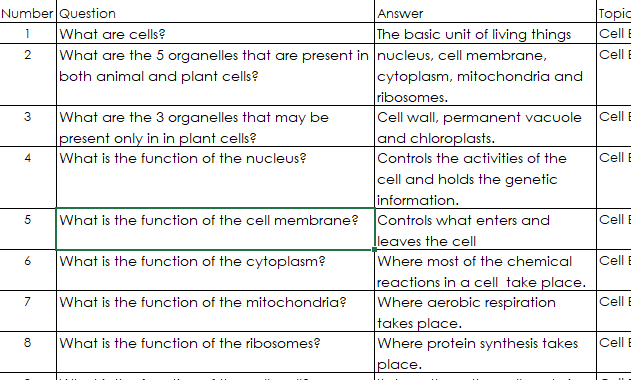

I’ve written before about the power of Core Questions in supporting students’ long term retention. Take a small part of your course, and turn it into a series of questions and answers. Try and keep them short and snappy, with no superfluous or redundant information. You might want to be judicious as well about high leverage ideas. There are some areas of your course which come up every single year, but also allow students to understand later concepts. Focus on those. A list from biology might look like the below:

You can see how tight the language is. As I’ve written about before, you might quibble with individual definitions’ wording here and there, but by and large it’s a good start.

- Take a small chunk and print it off

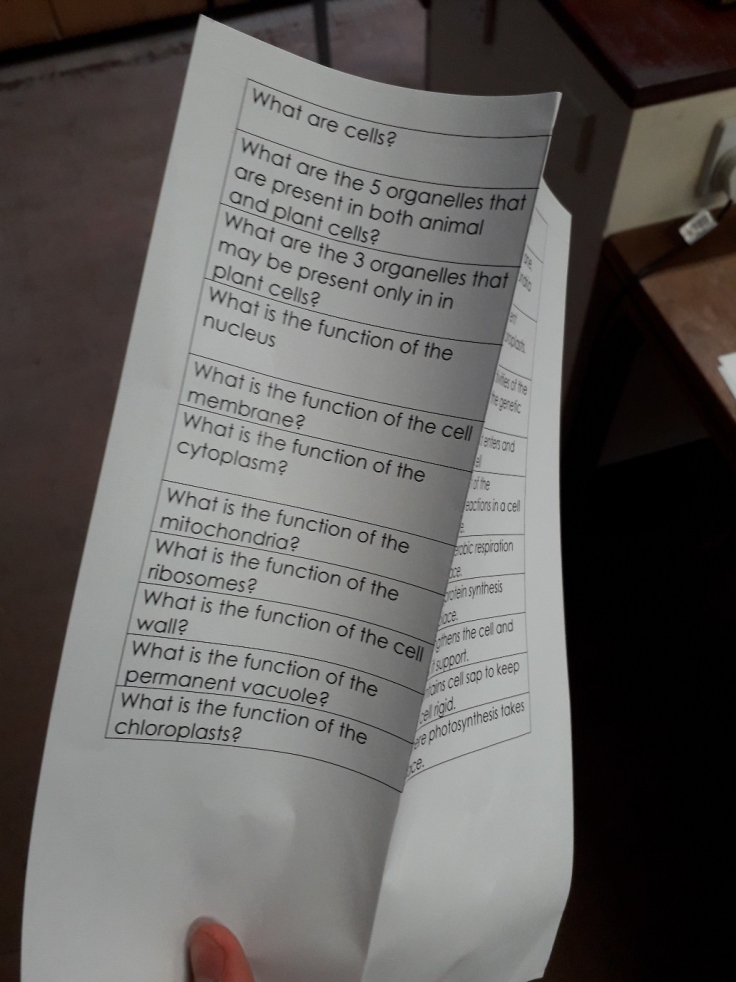

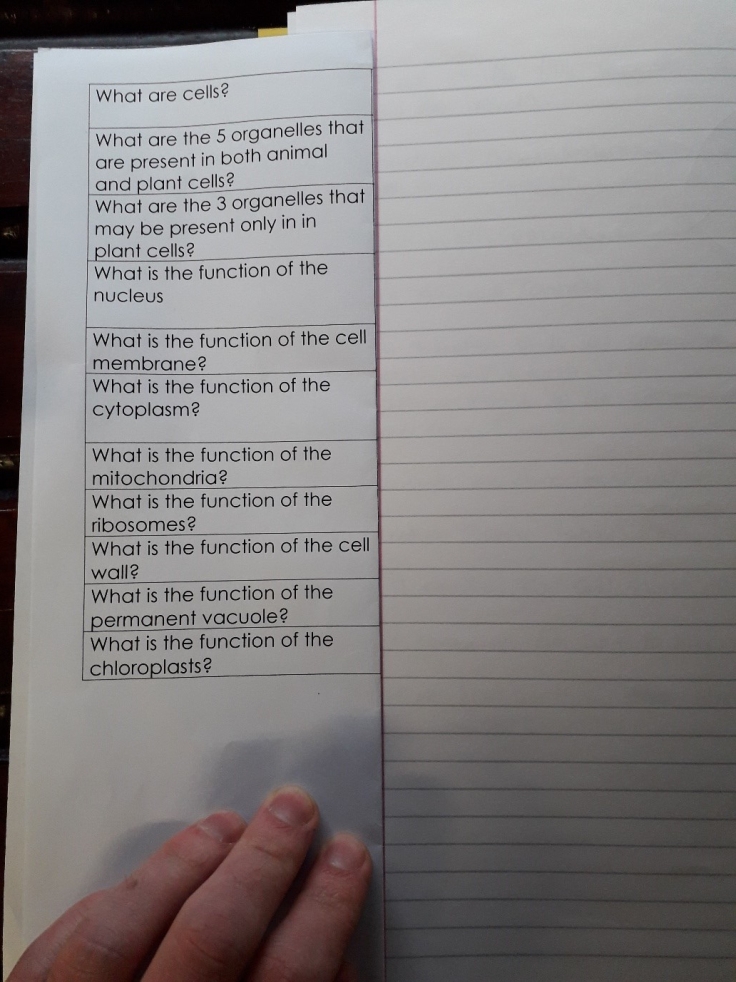

Choose a section that is both coherent in terms of content, but also manageable in terms of amount. Print it off nice and big, and fold it vertically so it looks like this:

- Show students how to use it

The goal here is to move to quizzing (retrieval practice) with the sheet really quickly. There are a number of different ways to do this, but so long as they are actively speaking or writing their answers (with writing being better) then they are doing good retrieval. With each of the below it may be best to encourage students to just try the first five and then slowly increase the number they are focussing on.

- Next to book and write

Pop the question sheet next to the book and write out the answers next to the questions. If you can’t remember one, leave it blank and wait till the end. Then get a different colour pen, turn the paper over and mark and make corrections. Rinse, repeat.

- Cut up

You or the students could cut the questions and answers up into mini-flashcards, with questions on the front and answers on the back. Students can then mix them up and use them for quizzing. Those of you who lovely glitzy resources could even make some kind of hat to mix them up in and pull them out.

- Verbal self-quiz

Both of the above work with individuals self-quizzing and speaking out their answers. I think on balance it’s better for students to write their answers, but speaking should work too.

- Peer-to-peer quiz

This can work really well with students working in pairs. However, there are two additional variables at play. The first is that it is more likely they will go off task and talk to each other, and the second is that if one student is asking the other student, only one student is actually doing retrieval practice. This potentially cuts effective learning time right down (if not entirely by half) so it’s worth considering.

- Don’t do it that way!

I guarantee at least one of your students will start trying to use the resources you give them badly. They’ll start highlighting, or just copying them out or just staring at them. They’ll say to you “this helps me sir” – it doesn’t. You’re the boss, you’re in charge. Get them quizzing.

- Circulate

Whilst all this is going on you need to be going round the room checking up on students, re-focussing their attention and helping them learn more. Some of the steps involved in that follow:

- Right is right

Students need to make sure they aren’t doing the classic “yeah that’s what I meant” thing. If they wrote x and not y, they need to be held accountable to that. You need to be really explicit with them that only right is right, and anything else isn’t good enough. If one student spends an entire lesson on one question just to make sure they get the correct phrasing: that’s not a bad use of time.

- Encourage

Students will go through periods of feeling like they haven’t got a clue and ones where they feel they are actually getting something. When they are in the former, remind them of the latter. When they are in the latter, remind them of the former and how proud they should be that they persevered through and have managed to really learn something.

“well done, that’s some great work there”

“you’re really getting this – I hope you’re proud of yourself!”

“yeah you got this, top job. Doesn’t that feel good?”

“see what you can do when you put your mind to it?”

“that’s some great work, but don’t give up now. I know you can do a bit more.”

I avoid using rewards, but do try to use praise for effort. Don’t praise activities that don’t deserve it, so if a student has done nothing for 40 minutes then spent 10 minutes working don’t praise them unreservedly, instead say things like “it’s good that you managed to do this work now, but it’s a massive shame you didn’t start earlier when I know you could have achieved so much.”

- Introduce variation

Once students start to master a list (and they will) introduce a bit of variation to maintain difficulty (see more here). Sometimes, all you need to do is change the order of the questions in the list to introduce enough difficulty as to maintain the challenge. Other times you might want to simply flip answers for questions and have students try to figure out the question from the answer. A little bit of rewording can go a long way too, saying things like “where does protein synthesis happen?” instead of “what is the function of the ribosomes?/where protein synthesis takes place.”

- Shake it up baby now

A room full of silent year 11s writing self-quizzes down three times a week for a year is probably not going to happen. Let’s be honest. You’ll definitely want to shake the routine up every so often, either by activities mentioned already in part 3, or by:

- Book an ICT room and have them do mini-quizzes via the retrieval roulette

- Give them questions as a semi-formal assessment to be done in silence and marked as a class

- A bit of whole class teaching if there is something that you think needs more explanation

- Leitner method work

- Some straightforward old exam questions

Every so often I get tempted to do games or a competition, but I think we need to be a bit wary around stuff like that. Students have an ability to win learning games without actually learning anything and competitions can often just serve as a massive source of distraction “sir, he’s looking at his notes!” but I suppose it’s up to you. Hopefully nobody unfollows this blog if I say it’s ok to do a game once in a while.

- Low and slow

I’ve written before about the tension between covering content and trying to be thorough. Using this route, you probably won’t finish the course. But put it like this: is there any point in finishing the course if they don’t remember anything?

- Hold the line

It’s not easy to teach like this. It’s damn hard work and you need to be on top of your game. You aren’t going to manage that every lesson, but you need to try, and not let it get you down if it flops now and then. I remember one class I had the students used to bicker among themselves. Every so often there had been a flare-up in the playground or whatever: no learning happened the lesson following. It is what it is, and you need to be realistic. It could be that, it could be the afternoon, it could be a full moon, it could be anything. Pick up, and get back on it tomorrow.

- A lesson for life

None of the above is ideal. It shouldn’t be the case that you have year 11s turning up on day one who don’t know anything. Sadly, it is the reality in many schools. So here’s the thing: if you did all of the above, but in year 7, what would your year 11 bottom set look like? If you got them quizzing and retrieving and working at home early as they power through an ambitious curriculum that motivates through fascinating content and a growing feeling of mastery, what would your year 11 bottom set look like? Do you like what you see? Well, you’ve got five years. Get to it.

UPDATE: 11/05/20

Amelia Kyriakides has made this excellent video showing how to use a number of the techniques outlined in this blog. It looks very student friendly and could make a massive difference to your students.

Final note: you could of course buy your class a set of knowledge quizzes. I don’t want this blog to be an advert for them as I know budgets are tight and I don’t think it’s appropriate for this blog anyway. But they will do a lot of the work for you, and the feeling of having a book completed and full of work will be powerful for your students as well. If you do want to order bulk copies, John Catt will do a discount.

5 Pingback